I am writing this message as an open letter to whoever will listen, as an apology to those who I have hurt, as a cry for help, and as a vision statement for my own life and future. I have had to overcome great shame and anxiety to even begin to write these “Confessions.”

For about a decade now (since 2013), I have had a dream, a vision, a desire to see a Transitional Living Worker Cooperative that is designed to help and hire those people who society regularly forgets, namely the so-called undeserving poor, the “junkies,” the formerly and currently incarcerated, and the homeless. I fit into each and every one of those categories, at one point or another in my life. My dream is for this Transitional Living Worker Coop (TLWC) to take in the people that I just mentioned, especially when they are at their “worst,” when they are at their “bottom.” By “take in,” I mean literally to provide housing in a large apartment complex with separate units for individuals, roommates, couples, and even families with children.

The TLWC will have programming of course: e.g. educational, job training, external counseling services, and peer coaches to help individuals with making it to all of the different appointments that are necessary to get one’s life back on track, be it going to public assistance appointments, court dates, or probation appointments, etc.

But unlike any program I have ever attended, we will not wish to be primarily funded by donations or government grants. I wish for this to be a for-profit worker cooperative where the residents of the program are also worker-owners in the coffee roasting business attached to the non-profit.

The goal is to help each incoming individual with a highly individualized plan to overcome whatever struggles they may have that contribute to their situation, be it addictions or mental health issues or just bad financial planning, while also addressing the structural injustices that keep marginalized people down. Namely, the goal will be for each individual to start working as soon as possible as a worker owner who literally owns part of the business and works to own their own housing unit as well.

Pay will be structured in such a way where the highest paid employee will not make more than three times the lowest paid employee. This is a far cry from most companies that have CEOs making up to 200 and 300 times their lowest paid employees. Even the lowest paid employees will immediately share in profit sharing. As such, there will not actually be any “employees,” because everyone will be a co-owner of the worker cooperative.

The theory is that when workers are treated well and are literally paid fairly and justly, that they will tend to give it their “all.”

When people have co-ownership of not only the business, but the housing that is tied to the business, then their job will not be “just a job.” Rather, it will be a community—a family to which they belong.

For so many people who are struggling with addiction or even depression (such as myself) the lack of a real tangible supportive community is a key factor in maintaining the hopelessness and isolation that keeps a person down. By belonging to this community, the individual will also feel a connection to a purpose that is greater than the individual, because we will all share in the profits, and we will all share in collective services that we choose to fund as a community—such as housing and shared automobiles.

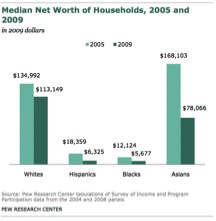

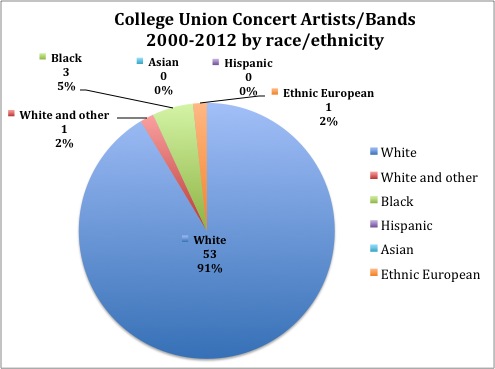

By having a just pay structure I hope to address the income inequalities that plague the racist history of this country.

As people may know, drugs do affect everybody, rich and poor, black, brown, and white, etc.. But the consequences of long term drug addiction absolutely do not affect everyone equally. Sure, a rich white kid may be just as likely as anyone to do drugs; but that rich white kid is much less likely to get convicted for stealing for drugs, for example.

As such, like most programs I have attended where most of the residents are poor, they will also statistically be more likely to be black or brown—that is, black or brown drug users are more likely than white drug users to suffer the legal and financial consequences of drug addiction or mental illness.

Therefore, by having both a just pay structure and a resident population that is disproportionately black, brown, and lower income (starting off), then we will also be addressing the racial wealth gap.

My dream is that going forward, in this day and age, that people will want to buy the coffee that we sell, because literally it will be financially supporting those people who not only have suffered from an unjust system but who may have lost hope and may have even become unwitting co-instruments of our own oppression.

This is my dream. This is my vision.

Sadly, I must confess that I am in no position to see this dream come into fruition…RIGHT NOW…

But I have to start somewhere…

So I am starting with a confession, accountability, and with a call for help. As cliché as it sounds, I see that:

I can’t help anybody if I can’t help myself.

Unfortunately, up to this time, I have been of little help to myself.

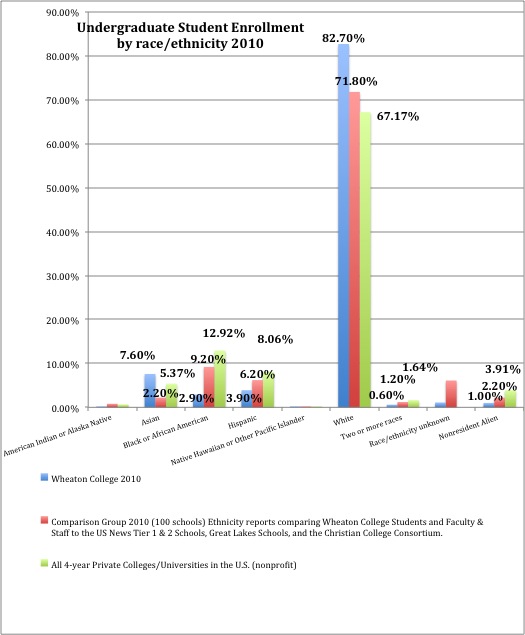

For several months, if not for the better part of the last year or so, I have struggled with undiagnosed depression, where I literally believed that “there is no way that I could ever achieve anything more than a minimum wage job.” I had believed that “I reached my peak in 2013 when I graduated from Wheaton College,” as the first person in my family to graduate from high school, earn a bachelor’s degree and pursue a master’s in seminary. I believed that when I relapsed back in 2015 that “I permanently lost all hope for my future.” I believed that “there is no way I could bounce back a second time.”

In 2008, I was at rock bottom, a convicted felon incarcerated at the Cook County Jail for retail theft related to my drug addiction. But I overcame that challenge; between 2008 and 2013 I remained clean and achieved many accomplishments, which culminated in studying under two of my heroes, Dr. James Cone and Dr. Cornel West at Union Theological Seminary.

In 2014 I had the privilege and honor of resisting racist and brutal police violence in Ferguson, Missouri alongside many of the grassroots activists who lived there.

But in 2015, when I underwent surgery for a burst appendix, I was prescribed opiates for the pain.

This was the beginning of the end for me…or so I had thought.

I quickly lost everything during my relapse, and in 2017 I was homeless with my wife in Chicago, Illinois. I had asked so many people for help and money via Facebook Messenger, and I am truly grateful for their help. But I am also sorry that I was not fully honest with those people that in addition to being homeless, I had also been struggling with an active addiction. Even though I used the money that people gave me to pay for shelter, it was still a waste to pay those gouged motel prices without a plan for attaining sustainable housing…and for that, I AM SORRY.

In 2018 I got clean again from drugs, but I never quite recovered psychologically. Furthermore, my wife and I lost our unborn child, just two days before he was scheduled to be born. Jerusalem Malcolm Qaddoumi-Aguilar was completely healthy according to tests and doctors. We were told, “these things happen,”—freak accidents resulting in stillbirth. Still, we pressed forward, determined to keep our recovery from drugs despite this tragedy.

Today, I have come to admit that for the past two years I have lived a very mediocre life, by not trying to apply to jobs that would utilize my full potential. I have been so debilitated by fear and shame that my mental voice would tell me that there is “no way that I would ever overcome the financial consequences of my 2015 relapse.” I have not posted a single Facebook or blog post in several years for the same reason of feeling inadequate and unworthy.

But something happened the other day that has affected me greatly. I had a conversation with a friend who knew me when I was rising above the challenges of my addiction that ended in 2008. This person just needed to remind me that I do have what it takes to overcome the challenges I am facing today. He reminded me that I am worthy of love and belonging and that I am capable of achieving my dreams or at least, I am capable of making a valiant pursuit of those dreams.

Admittedly, I am still not in a stable financial situation right now, but neither is much of the country due to COVID-19. So I must be considerate of that fact. At the same time, my situation is drastic, as I am struggling each and every day just to make enough money to have a place to sleep at night.

This time, I am not homeless because of drugs, but because after losing my job in 2019, I had been debilitated by shame and fear to the point where I believed that it was not worth trying to apply for jobs anymore. Some may see that as a cop-out, but it was not, for I truly and sincerely felt hopeless and unworthy.

But today, I am committed to trying everything I can to start somewhere, be it minimum wage, entry-level, or otherwise.

I will start somewhere and I will face each challenge as it comes, and I will grow. I will not give in to the inner voices that tell me to “give up.”

I will not give up, and I will not settle for mediocrity.

I will continue to write and I will share my writing with the hopes of getting better at this craft, so that one day it may be the beginning of the funding for my dream of the Transitional Living Worker Coop.

Please, if anyone knows of any job opportunities, I am desperately looking for work.

I do have a past, but I am not defined by my past. At the same time, I am driven by my past…driven to overcome the challenges I face, because I have overcome them before…and I am driven to build something that will help others overcome those same challenges as well.

I am also looking for housing. Currently, I am doing everything I can to hustle to pay for a motel in Rockland County, NY, but this is not sustainable. Therefore, unlike in 2017, I do have a plan to attain sustainable housing: This week I overcame my anxiety and negative inner voices, and I applied to several jobs in Rockland County…and I will continue to apply to many more. I hope to hear something from those jobs soon. I have sought help with Catholic Charities in Rockland County and with the Department of Social Services (DSS), but those were dead ends for continued housing assistance.

At this point, I need to find a person who is willing to accept payment from DSS in order to receive rental assistance from social services. They will cover up to $500 per month for rent.

I hope and pray I find both housing and employment soon.

I will do everything I can to help myself today, with the dream of doing everything I can to help others like me tomorrow.