My research partner, Laura Becker, and I sought to answer the question: “To what extent does race affect students of color at Wheaton College (Illinois)?” As the former Executive Vice President of Community Diversity on Wheaton’s Student Government, I was constantly fighting an uphill battle with students who denied there was a “race problem” at Wheaton. The goal of our study was to demonstrate with empirical data if a problem did in fact exist—because Wheaton will never adequately address this problem if most students believe that it does not exist.

As such, we conducted a survey-based study of the daily race-related experiences of students at Wheaton. Specifically, we sought to measure the prevalence of racial microaggressions and their effects on students at Wheaton. Similar studies have been conducted at various types of institutions, but none, to our knowledge, have been conducted in an exclusively evangelical institution of higher learning. Below is a summary of the larger paper entitled: The Prevalence of Racial Microaggressions at Wheaton College and Implications for Broader Society (Aguilar and Becker 2013).

Our research hypothesis was that race has a negative effect on the experiences of students of color at Wheaton College. That is, given prior research on microaggressions, students of color will be more likely than white students to be “stressed, upset, or bothered,” by the prevalence of racial microaggressions at Wheaton College. The null hypothesis is that students of color are not any more or less affected by racial microaggressions than white students at Wheaton.

WHAT ARE RACIAL MICROAGGRESSIONS?

While the elements of racism are almost impossible to enumerate, a growing body of literature suggests that racial microaggressions can have substantial adverse effects on the experiences of students and faculty of color in higher education (Solorzano, Ceja, and Yosso 2000; Sue, Capudilupo, and Holder 2008; Pittman 2012).

Racial microaggressions have been defined as, “brief and commonplace daily verbal, behavioral, and environmental indignities, whether intentional or unintentional, that communicate hostile, derogatory, or negative racial slights and insults to the target person or group” (Sue, Capodilupo, et al. 2007:331). Additionally, “Racial microaggressions refer to the racial indignities, slights, mistreatment, or offenses that people of color may face on a recurrent or consistent basis. Racial microaggression may represent a significant source of stress endured by people of color [emphasis added]” (Torres-Harding et al. 2012:153). These definitions of racial microaggressions were used to study the extent and effect of such interactions at Wheaton College.

While they may seem trivial, researchers have found that microagressions can, “assail the mental health of recipients” (Sue, Capudilupo, and Holder 2008), “create a hostile and invalidating campus environment” (Solorzano, Ceja, and Yosso 2000), “perpetuate stereotype threat” (Steele, Spencer, and Aronson 2002), “create physical health problems” (Clark, Anderson, Clark, and Williams 1999), and “lower work productivity and problem-solving abilities” (Dovidio 2001; Salvatore and Shelton 2007). The negative consequences of microaggressions may not manifest immediately, but numerous microaggressions over a period of time can have the above consequences for recipients.

DATA AND METHODS

Data was collected through a Student Government-sponsored web-based survey, which was emailed to all undergraduate students at the college. The survey was created on Survey Monkey and available for one week for students to complete online. The response rate was approximately 41% or 992 out of 2,400 undergraduate students. Total students of color equaled: 226 (≈22.8%); Total white students equaled: 766 (≈77.2%). It is significant that our response rate for students of color was over 50% of the students of color at the college. This will allow us to be more confident in generalizing the experiences of respondents to other students of color at Wheaton College. The demographics of the respondents (N=992) are representational of races, genders, majors, and backgrounds at institutions similar to Wheaton College, specifically, to other colleges in the Council for Christian Colleges and Universities (CCCU). Thus, these findings will have implications for the experiences of students of color at other CCCU schools as well.

The survey included a 30-item scale adapted from existing microaggression scales in the relevant scholarly literature. Items were reworded to make them specific to Wheaton College, and some items were added to address the faith aspect of Wheaton. For each item presented, respondents were asked to indicate how often they encountered it on a four-point Likert-type scale (1- never, 2 – a little/rarely, 3 – sometimes/a moderate amount, 4 –often/frequently). Samples of statements on the survey include:

- People at Wheaton College say that there are bigger things to worry about than issues related to race.

- People at Wheaton College question the legitimacy of a worship or prayer style that is familiar to my racial/ethnic background.

- At Wheaton College, people of a race/ethnicity other than my own are impressed by “how articulate” I am.

- People at Wheaton College tell me I should focus on the Gospel instead of focusing on race.

- People at Wheaton College say or imply that people of my racial/ethnic background are admitted to the college because of affirmative action.

- At Wheaton College, I see few people of my racial/ethnic background.

To measure if the item was perceived as a racial microaggression, we needed to measure the degree to which the experience was “stressful, upsetting, or bothersome.” Thus, if a respondent indicated the positive occurrence of an item (1 or greater on the occurrence scale), he or she was asked to indicate how stressful, upsetting, or bothersome the experience had been (1 – not at all, 2 – a little, 3 – moderate level, 4 – high level).

The survey responses (N=992) were analyzed statistically using PASW/SPSS, looking for themes and relationships in the data. Two subscales were created to measure the average levels of occurrence (MCROCCUR) and the degree to which students are affected by microggressions (MCRFX) at Wheaton. That is, two subscales were created that measured each student’s average score for the occurrence and effects of all 30 items on the survey. For example, if I answered 2 (a little/rarely) for 10 items, 3 (sometimes/a moderate amount) for 10 items, 1 (never) for 5 items, and 4 (often) for 5 items, then my average score for MCROCCUR would be [(2×10)+(3×10)+(1×5)+(4×5)]/30 = 2.5, which is greater than “a little/rarely” but not quite “sometimes/a moderate amount.” We would interpret this number by saying that my average score for the 30 racial microaggressions on the survey was more than “a little/rarely.” Similarly, the MCRFX subscale measures a student’s average score for the degree to which the items were “stressful, upsetting, or bothersome.” If a student indicated that they did not experience an item on the survey, then the MCRFX score for that particular item would be “0” since not experiencing an item would mean that they had no negative effects related to that item.

DATA ANALYSIS

Statistical analysis of the data showed a higher prevalence of both racial microaggressions and negative effects among students of color at Wheaton compared to white students. A three-model linear regression analysis confirmed our hypothesis that race has a negative effect on the experiences of students of color at Wheaton compared to white students. The coefficients in Model 3 of Table 1 allow us to predict that, holding gender and number of years completed as a student at Wheaton constant, Black or African American students experience a .727 increase, compared to whites, in the mean scores for the occurrence of all 30 microaggressions presented in the survey. This regression coefficient (B) is statistically significant at the .001 level. For Latina/o and Asian students, we can predict that, holding gender and years constant, there are increases of .472 and .497, respectively, in MCROCCUR subscale means compared to whites. These coefficients are statistically significant at the .001 level. Students of two or more races and nonresident or resident aliens had lower regression coefficients than black and Latina/o students, but still showed an increase of experiencing racial microaggressions, and they were statistically significant at the .001 level. The coefficient for female students was not statistically significant. However, the coefficient for “years completed” tells us that that for every year completed at Wheaton, there is an increase of .045 in the MCROCCUR subscale for students of color. The models presented are statistically significant and confirm that being a nonwhite student will increase the number of microaggressions that a student experiences while at Wheaton College. Each race/ethnicity listed in the models is compared to white students.

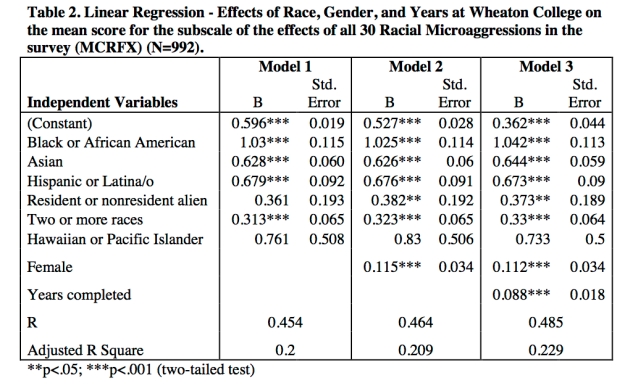

MCRFX measured the average degree to which the microaggressions were “stressful, upsetting, or bothersome,” for each student. In Model 3 of Table 2, we could predict that, holding gender and number of years completed constant, Black or African American students, compared to whites, experience a 1.042 increase in levels of being “stressed, upset, or bothered” by the occurrence of the 30 microaggressions presented in the survey. This regression coefficient (B) was statistically significant at the .001 level. According to this data, African American students experience significantly higher levels of being stressed, upset or bothered due to racial microaggressions more than any other race or ethnicity at Wheaton College. For Latina/o and Asian students, we can predict that, holding gender and years constant, there will be increases of .673 and .644, respectively, in MCRFX subscale means compared to whites. These coefficients are statistically significant at the .001 level. This means that both Latina/o and Asian students are more likely to experience the negative effects of racial microaggressions than white students at Wheaton. Students of two or more races and nonresident or resident aliens had lower regression coefficients than black and Latina/o students, but still showed an increase in experiencing the negative effects of racial microaggressions compared to white students, and they were statistically significant at the .001 and .05 levels, respectively. Female students experienced a slight increase in MCRFX means compared to males when race and years completed are held constant. We also see that with each increase in number of years completed at Wheaton, there is an increase of .088 in the MCRFX subscale – and this is significant.

A comparison of MCROCCUR subscale means found that 65% of Black or African American students, 43.75% of Hispanic or Latina/o students, 40% of Asian students, 28.99% of mixed race students, and 14.29% of nonresident or resident alien students at Wheaton college had an average score for experiencing the racial microaggressions on the survey that was more than “A little/rarely.” Only 4.90% of white or Caucasian students had an average MCROCCUR score greater than “A little/rarely.”

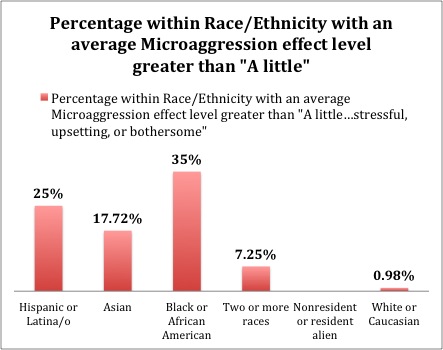

Likewise, a comparison of MCRFX subscale means found that 35% of Black or African American students, 25% of Hispanic or Latina/o students, 17.72% of Asian students, and 7.25% of mixed race students at Wheaton college had an average score for the effects of the racial microaggressions on the survey that was more than just “A little… stressful, upsetting or bothersome.” Less than 1% of white or Caucasian students had an average MCRFX score greater than “A little.”

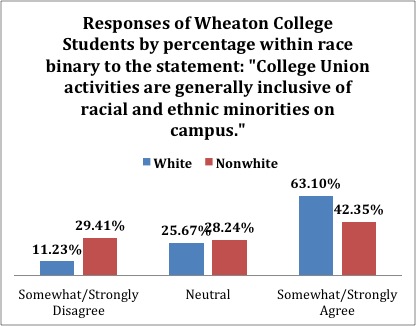

An additional question attempted to evaluate the level of “environmental/institutional” racism, which yielded the following results. Students of color (29.41%) were significantly more likely than white students (11.23%) to “Somewhat or Strongly Disagree” with the statement: “College Union activities are generally inclusive of racial and ethnic minorities on campus.” Similarly, students of color (42.35%) were significantly less likely than white students (63.10%) to “Somewhat or Strongly Agree” with the same statement. This data shows that white students are less likely to perceive the negative experiences of students of color related to the lack of an inclusive and welcoming campus environment.

DISCUSSION

This study shows that while many students of color at Wheaton College are unaffected by racial microaggressions, a significant percentage not only experience racial microaggressions but are negatively affected by them as well. These students of color must not be ignored, as their experiences are symptomatic of the difficulty of attending a majority white college as a racial minority. With so few students of color at Wheaton already, it is significant that the majority of African-American students (65%) and 43.75% of Hispanic or Latina/o students, 40% of Asian students, 28.99% of mixed race students, and 14.29% of nonresident or resident alien students experience microaggressions more than just “a little/rarely,” compared to only 4.90% of white students. It is even more significant that sizable numbers of racial and ethnic minorities (35% of Black or African American students, 25% of Hispanic or Latina/o students, 17.72% of Asian students) are, on average, more than just “a little” stressed, upset, or bothered by the occurrences of these microaggressions. As stated earlier, microaggressions can have significant negative effects not only on one’s experience, but on one’s physical and mental wellbeing as well. Thus, the data validates our research hypothesis that, race has a negative effect on the experiences of students of color at Wheaton College. In other words, it is undeniable that racial and ethnic minorities at Wheaton are still more likely than white students to have negative college experiences due to their race.

The unique contribution of this study is the particular application of a racial microaggression scale to an evangelical Christian institution. Because of significant similarities between the social demographics of respondents in the study and students at Wheaton College and other CCCU schools, these findings suggest that evangelical colleges have a significant amount of work to do to become welcoming institutions for their nonwhite students.

One may ask why statements such as “we should focus on the Gospel instead of focusing on race,” are upsetting to students of color. As a student of color, I have heard this sentiment from white students many times, and what it tells me is that white students do not see the connection between the experiences of their nonwhite sisters and brothers in Christ and the Gospel. The statement above invalidates the belief that racial reconciliation and equality are part of focusing on the Gospel. In other words, presumably well-meaning white students invalidate my struggles as a student of color by relegating the need to address them as unimportant and unrelated to being a follower of Christ. This, of course, is extremely frustrating when it happens over and over and over.

Similarly, statements such as “people of color are admitted to the college because of affirmative action,” or “we should not lower academic standards to increase diversity,” imply that people of color are less intelligent and/or less qualified than white students. I hope it is obvious why this would be stressful, upsetting, or bothersome to students of color who have to hear this on a regular basis.

WHAT TO DO?

If Wheaton College and presumably other CCCU schools do not address the prevalence of racial microaggressions and their negative effects on students of color, then racial diversity will continue to increase at an excruciatingly slow rate. Students of color who feel alienated and unwelcome while at Wheaton will be less likely to recommend their alma mater to future students of color, thereby decreasing the potential for diversifying Wheaton in the future. The findings of this study also imply the need for structural reform at the top levels of CCCU colleges and universities. Specifically, four characteristics are commonly thought to be necessary for nurturing a positive campus racial climate:

- The inclusion of students, faculty, and administrators of color;

- A curriculum that reflects the historical and contemporary experiences of people of color;

- Programs to support the recruitment, retention, and graduation of students of color; and

- A college/university mission that reinforces the institution’s commitment to multiculturalism (Solorzano et al. 2000:62)

Addressing college campuses about racial microaggressions should not be solely the duty of the faculty members of color, but should be institutionalized components of college orientations, handbooks, and training for staff such as counselors and student leaders such as resident assistants. Because even seemingly trivial microaggressions have significant consequences for their recipients, members of the majority race at CCCU schools should be introduced to the concepts of racial microaggressions to broaden their understanding of the detrimental effects of these actions and words on students of color.

An infrastructure must be created on college campuses to address racism and racial microaggressions as common practice. Regular classes and forums on race and racism, some optional and some mandatory, would be part of this infrastructure, along with required, in-depth training for faculty and staff members to increase their awareness and sensitivity in areas of racial diversity and inclusion. Additional training would allow faculty members and even staff such as resident assistants to regularly and successfully facilitate conversations about race, both inside and outside the classroom (Minikel-Lacocque 2012).

Campus infrastructure addressing race relations must be focused not only on blatant acts of racism but on the seemingly innocuous forms of microaggressions as well. The idea of hidden or subtle racism should be introduced in classes, student orientations, support groups, and social settings so that racial microaggressions can become part of the common conception of racism.

According to Minikel-Lacocque (2012), White students, faculty, and staff in particular must become well versed in the concept of common, often overlooked racial microaggressions. By valuing the voices of people of color and implementing the concept of racial microaggressions into our common discourse on race relations, we can widen the dialogue and move toward a more harmonious racial campus climate at CCCU institutions such as Wheaton College.

APPENDIX 30 Racial Microaggression Items

- At Wheaton College, I feel ignored in the classroom because of my race/ethnicity.

- People at Wheaton College say that there are bigger things to worry about than issues related to race.

- People at Wheaton College question the legitimacy of a worship or prayer style that is familiar to my racial/ethnic background.

- People at Wheaton College assume I listen to a particular kind of music because of my race/ethnicity.

- I feel like people at Wheaton College see me as “exotic” in a sexual way because of my race/ethnicity.

- At Wheaton College, people of a race/ethnicity other than my own are impressed by “how articulate” I am.

- I notice that my Wheaton College class worship band does not include worship styles familiar to my cultural background.

- At Wheaton College, sometimes I feel like my contributions are dismissed or devalued because of my racial/ethnic background.

- People at Wheaton College tell me I should focus on the Gospel instead of focusing on race.

- I am made to feel as if the cultural values of another race/ethnic group at Wheaton College are appreciated more than my own.

- People at Wheaton College imply or state that I am not like other people of my racial/ethnic background.

- Other people at Wheaton College view me in an overly sexual way because of my race/ethnicity.

- Sometimes, people at Wheaton College assume that I am a foreigner because of my race/ethnicity.

- At Wheaton College, I see few people of my racial/ethnic background.

- At Wheaton College, sometimes I feel as if people look past me or act like they don’t see me because of my race/ethnicity.

- People at Wheaton College tell me that they are not racist or prejudiced because they have friends from different racial/ethnic backgrounds.

- People at Wheaton College react negatively to the way I dress because of my racial/ethnic background.

- People at Wheaton College assume I am good at Math because of my race/ethnicity.

- Other people hold sexual stereotypes about me because of my race/ethnicity.

- Sometimes I feel like people at Wheaton College ask me where I am from, expecting to hear a location outside of the United States because of my race/ethnicity.

- I notice that there are few people of my racial/ethnic background who attend churches that are accessible to me at Wheaton College.

- At Wheaton College, I feel like my perspective on racial issues is dismissed or devalued because of my racial/ethnic background.

- People at Wheaton College tell me that they are not racist or prejudiced even though they, intentionally or unintentionally, exhibit example(s) of racist or prejudiced behavior.

- People at Wheaton College say that the college should not lower standards just to increase racial/ethnic diversity.

- I feel like people assume I would not be interested in a particular activity at Wheaton College because of my race/ethnicity.

- When I interact with authority figures at Wheaton College, they are usually of a different racial/ethnic background.

- When I describe a difficulty related to people in my racial/ethnic background, people at Wheaton College tell me that everyone can get ahead if they work hard.

- People at Wheaton College say or imply that people of my racial/ethnic background are admitted to the college because of affirmative action.

- It is hard to relate to a professor at Wheaton College because of our racial/ethnic backgrounds.

- If someone makes a racially insensitive comment in class, I struggle with whether or not I should say something about it in class.

REFERENCES (Cited in paper)

Clark, Rodney, Norman B. Anderson, Vernessa R. Clark, and David R. Williams. 1999. “Racism as a Stressor for African Americans: A Biopsychosocial Model.” American Psychologist 54(10):805-816.

Christerson, Brad, Korie L. Edwards, and Michael O. Emerson. 2005. Against all odds : the struggle for racial integration in religious organizations. New York: New York University Press.

Dovidio, John F. 2001. “On the Nature of Contemporary Prejudice: The Third Wave.” Journal of Social Issues 57(4):829-849.

Duncan, Garrett Albert. 2005. “Critical race ethnography in education: narrative, inequality and the problem of epistemology.” Race, Ethnicity & Education 8(1).

Emerson, Michael O., and Christian Smith. 2000. Divided by faith: evangelical religion and the problem of race in America. Oxford; New York: Oxford University Press.

Emerson, Michael O., and Rodney M. Woo. 2006. People of the dream: multiracial congregations in the United States. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press.

Hatuqa, Dalia. 2006. “Evangelical Colleges Gaining Popularity.” The Times of Northwest Indiana, April 9. Retrieved (http://www.nwitimes.com/news/local/article_7ecda610-5f17-5805-8411-d9917172fddc.html).

Howell, Brian. 2012. “Racism without Racists.” The Soapbox. Retrieved (http://brianhowell.blogspot.com/2012/02/racism-without-racists.html).

Joeckel, Samuel, and Thomas Chesnes. 2012. The Christian college phenomenon: inside America’s fastest growing institutions of higher learning. Abilene, Tex.: Abilene Christian University Press.

Kaiser, Cheryl. 2001. “Stop Complaining! The Social Costs of Making Attributions to Discrimination.” Personality social psychology bulletin 27(2):254–63.

Lee, D. John, Alvaro L. Nieves, and Henry Lee Allen. 1991. Ethnic-minorities and evangelical Christian colleges. Lanham, Md.: University Press of America.

McCabe, J. 2009. “Racial and Gender Microaggressions on a Predominantly-White Campus: Experiences of Black, Latina o and White Undergraduates.” Race, gender class 16(1/2):133–51.

Minikel-Lacocque, Julie. 2012. “Racism, College, and the Power of Words: Racial Microaggressions Reconsidered.” American Educational Research Journal 56(3):1-30.

Nadal, Kevin L. 2011. “The Racial and Ethnic Microaggressions Scale (REMS): Construction, reliability, and validity.” Journal of Counseling Psychology 58(4):470–80.

Passel, Jeffrey, and D’Vera Cohn. 2008. U.S. Population Projections: 2005–2050. Pew Research Center. Retrieved (http://www.pewhispanic.org/files/reports/85.pdf).

Pierce, C. M. 1977. “An Experiment in Racism: TV Commercials.” Education and urban society 10(1):61–87.

Pittman, Chavella T. 2012. “Racial Microaggressions: The Narratives of African American Faculty at a Predominantly White University.” Journal of Negro Education 81(1):82–92.

Princeton Review, The. 2013. Wheaton College Review. Retrieved (http://www.princetonreview.com/WheatonCollegeIL.aspx).

Reisberg, Leo. 1999. “Enrollments Surge at Christian Colleges.” Chronicle of Higher Education 45(26):A42–A44.

Ryken, Phillip. 2012. “Strategic Priorities.” Wheaton College, May 19. Retrieved (http://www.wheaton.edu/About-Wheaton/Leadership/Strategic-Priorities/~/media/Files/About-Wheaton/Strategic-Priorities-051812.pdf).

Salvatore, Jessica, and J. Nicole Shelton. 2007. “Cognitive Costs of Exposure to Racial Prejudice.” Psychological Science 16(5):810-815.

Smith, William A., Walter R. Allen, and Lynette L. Danley. 2007. “‘Assume the Position . . . You Fit the Description’.” American Behavioral Scientist 51(4):551–78.

Solorzano, Daniel, Miguel Ceja, and Tara Yosso. 2000. “Critical Race Theory, Racial Microaggressions, and Campus Racial Climate: The Experiences of African American College Students.” The Journal of Negro Education 69(1/2, Knocking at Freedom’s Door: Race, Equity, and Affirmative Action in U.S. Higher Education):60–73.

Steele, Claude M., Steven J. Spencer, and Joshua Aronson. 2002. “Contending with Group Image: The Psychology of Stereotype and Social Identity Threat.” Advances in Experimental Social Psychology 34:389-402.

Sue, Derald Wing, Christina M. Capodilupo, et al. 2007. “Microaggressions in Everyday LIfe: Implications for Clinical Practice.” American Psychologist 62(4):271-286.

Sue, Derald Wing, Christina M. Capodilupo, and A.M.B. Holder. 2008. “Racial Microaggressions in the Life Experience of Black Americans.” Professional Psychology: Research and Practice 39(3):229-336.

Sue, Derald Wing, Annie I. Lin, et al. 2009. “Racial Microaggressions and Difficult Dialogues on Race in the Classroom.” Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology 15(2):183-190.

Sue, Derald Wing. 2010. Microaggressions in Everyday life: Race, Gender, and Sexual Orientation. Hoboken, N.J.: Wiley.

Sue, Derald Wing, David P. Rivera, et al. 2011. “Racial Dialogues: Challenges Faculty of Color Face in the Classroom.” Cultural diversity & ethnic minority psychology 17(3):331–40.

Swim, Janet. 2003. “African American College Students’ Experiences with Everyday Racism: Characteristics of and Responses to These Incidents.” Journal of Black Psychology 29(1):38–67.

Torres-Harding, Susan, Alejandro L. Jr Andrade, and Crist E. Romero Diaz. 2012. “The Racial Microaggressions Scale (RMAS): A new scale to measure experiences of racial microaggressions in people of color.” Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology 18(2):153–64.

Yancey, George A. 2010. Neither Jew nor gentile: exploring issues of racial diversity on Protestant college campuses. New York: Oxford University Press.

Hi Danny, I really appreciate the work you’ve put into this stufy.

The deadline for proposals is 2 days gone now (1/15/14) but you might see if this conference would still accept your research: https://www.ncore.ou.edu/en/ncore2014/callforpresentations/

If not, maybe for 2015?

LikeLike

Hi Ashley!

thank you so much for the link! It’s been a crazy week. Sorry for the delayed response. I’ll certainly look into this and other conferences!

LikeLike

I’m not an expert in evaluating research data, but your approach seems cogent to me. I would hope that your conclusions would be taken seriously by the college as well as other institutions struggling to be multicultural.

LikeLike

Thanks mebanks! I would hope that the findings would be taken seriously too. We shall see. I was actually recently contacted after I posted this blog asking to resubmit my data to the school. Let’s see what they do with it! I’m not technically an expert either. But my Social Research Prof is, and he did a great job at preparing Laura and I for this study. He had some pretty rigorous requirements to do the project. Ha! At the time, I know Laura and I were both frustrated with how strict he was grading us on the preliminary research, but it paid off because we got an A in the end! Thanks again!

LikeLike

Have you been able to present your findings to faculty and administrators at Wheaton? If so what was the reaction? If not, you should look for an avenue to present these findings one possible avenue would be at the Student Congress on Racial Reconciliation at Biola University that takes place in February.

LikeLike

Hi Joel!

Upon completion of the initial study and essay, I emailed the full study to several professors, staff members, students, and administrators, all the way to the highest office at the college. For reasons untold to me, I only received feedback from my Sociology and Anthropology Professors and several students of color (and 1 or 2 white students, half of which vehemently disagreed with my findings).

I must admit that I was disappointed that no one in the Office of Institutional Research responded to my emails, wherein not only did I submit my and my research partner’s final paper, but our whole raw data set as well.

Again, a handful of professors gave positive feedback (including my social research prof who gave us an ‘A’ for the study!), but zero administrators and relevant staff members had anything to say about this study. I’ll admit that there is some work being done at Wheaton on these issues (by a select few of highly dedicated members of the community), but the institution as a whole, up to and including the Board of Trustees, seems disturbingly patient and relaxed in their efforts to create a welcoming and inclusive campus environment for students of color (and anyone who doesn’t “fit the mold” for that matter).

Thus, I posted our findings on my blog, because I believe they could benefit people who care to create welcoming and inclusive campus environments not only at Wheaton College, but at other CCCU schools as well.

I am definitely interested in presenting the full paper, and/or Prezi presentation, at other venues if it will further the causes of Diversity and Inclusion. I looked up SCORR and am interested in hearing more about the prospects of presenting at this venue. Who would you suggest I contact to investigate this possibility? My email address is: danny.aguilar@my.wheaton.edu

Also, if you get a chance, I’d be interested to hear what you think about this related blogpost: https://thetatteredrose.wordpress.com/2013/12/09/for-christ-and-his-white-kingdom-an-open-letter-to-the-wheaton-college-community-on-white-supremacy-on-campus/

LikeLike

Reblogged this on The Tattered Rose and commented:

The Prevalence of Racial Microaggressions at Wheaton College: A Sociological Study

LikeLike